Grief is not monolithic nor unilateral. It’s multi-faceted. It’s nuanced and personal. The light fractures off my brokenness in a different array than yours. The colors that exude are much more than black and white.

Grief is like a Venn diagram. There is a vast expanse that is empty and feels void. Most of the tears shed in that space go unwitnessed. But like all terra incognita, exploration is required to create a chart and a map that might be helpful to someone following in my footsteps.

In the Venn diagram, it’s the overlap that brings insight. When my grief crosses over into your space, new acumen develops. New discoveries get added as a reference point on the new map. Intentional documentation plays a big role here.

In my newfound identity, I have a chance to take new risks and invest in myself in ways I never could before. The stakes aren’t quite so high when it’s just me on the line. I risked everything once and lost it all. So what’s stopping me from trying again? There’s a whole lot less to bet, and a world of payouts to anticipate. It’s like I’m playing with house money.

I recently joined a writing group called hope*writers. I decided it was time to invest in my voice as a writer and see where the road would lead. I have just scratched the surface that this resource has to offer but have already begun mining it as a valuable claim. I have connected with other writers who are telling their stories and taking note where another story overlaps with mine.

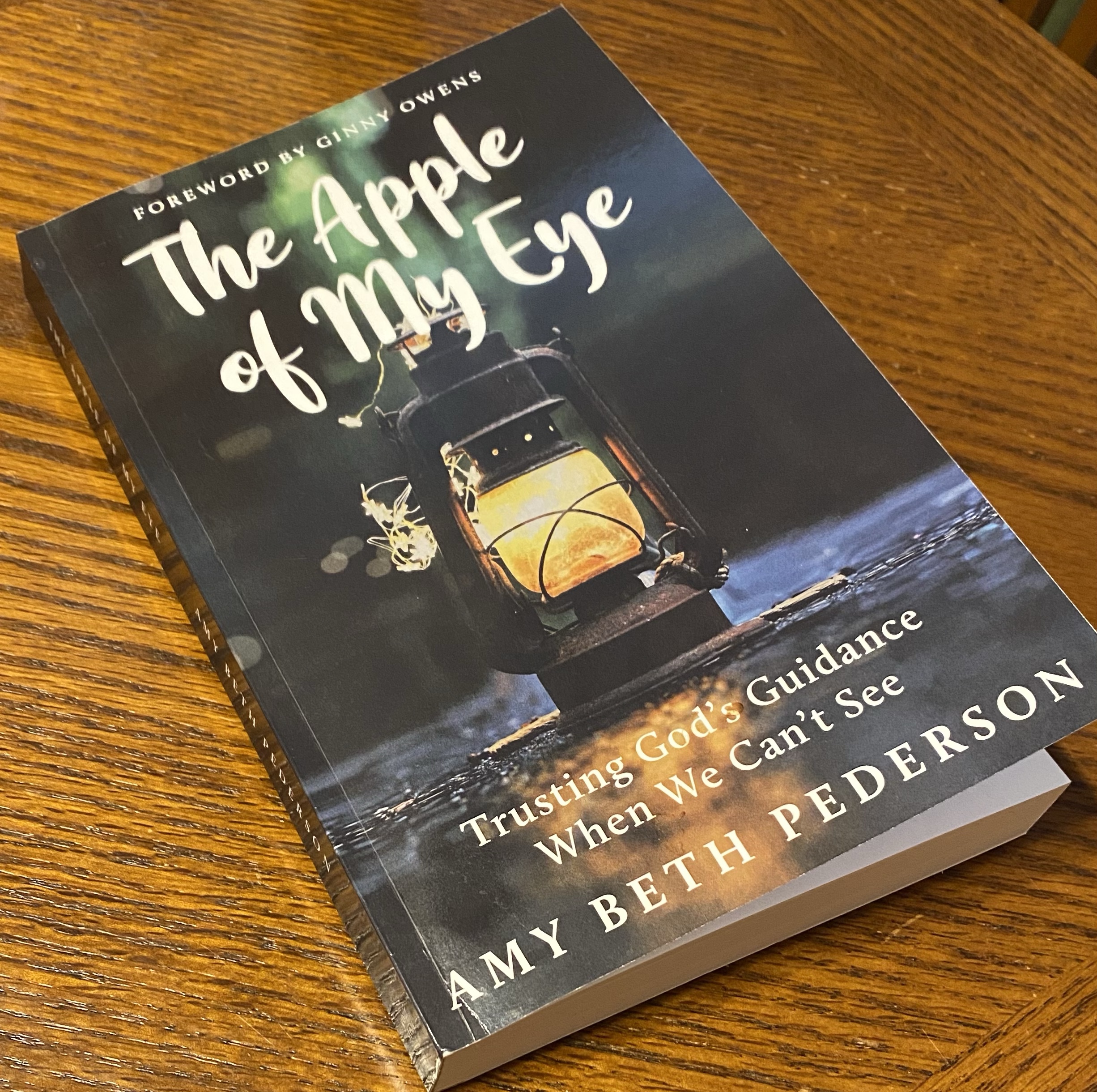

All loss must be grieved. Writers are inclined to use their words to express the resultant sorrow. Amy Peterson is one of those authors.

I just finished her book, The Apple of My Eye. It is so beautifully written, I felt compelled to pen a short review and recommendation.

Amy lost her husband this year to a rare form of ocular cancer. With small children at home, it was an even more complicated ordeal to manage. And while the details of her loss are not equivalent to mine, the description of the emotion of five years of treatment and loss sparks deja vu.

The biggest value of this book for me is summed up in these four words in chapter 36, page 211:

“I did my best.”

Any caregiver knows the self-doubt that insidiously creeps into those thoughts that begin with, “what if…”

- “What if I had kept up with her regular cancer screenings?”

- “What if I hadn’t risked our life savings and future security to chase a dream?”

- “What if I didn’t want so much?”

This hamster wheel of second guessing will keep on spinning as long as I volunteer to propel it. And at some point, when exhaustion sets in, its time for me to get off the wheel and accept that, yes, I did my best. There will always be things I wish I did differently and wish I could have changed. But I can’t live life backward.

Sometimes it takes hearing it from someone else, an experienced voice outside of my own head, to affirm what I want to know as true. To hear from someone who knows how to effortlessly describe what the inside of a hospital room smells like or the title of the hymns that the elderly man was playing on the piano in the hospital atrium, there is no substitute for this kind of possession.

All loss isn’t equal, but all loss must be grieved. In my conversations with friends this year, I glean from those who have lost a marriage, a job, and even a pet. There is no spectrum of ranking loss in terms of importance. Your loss is yours. It is loss, regardless. I can’t, nor should I try to minimize my loss by comparing it to yours.